Now that the Renaissance Community Cooperative has closed, F4DC is getting lots of requests for information on every aspect of the eight year process of opening, operating, and closing the store. This booklet, created to mark the grand opening of the RCC in November 2016, captures the first part of the story, detailing the five year struggle to organize the community, raise the money, and build the store. Even though the RCC has closed, we still think it was more than a grocery store to the thousands of people who connected to the effort. And there are valuable lessons to be learned from every step of the process.

A Date Certain: Lessons from Limited Life Foundations

Back in 2010, co-founder Ed Whitfield and I were acutely aware of the intertwining economic, social, and ecological crises unfolding around us. It struck us that if we wanted to help ensure the survival of humans and other beings on the planet, we might want to dive in wholeheartedly with all the resources of the Fund for Democratic Communities, rather than dribbling a few dollars here and there over an extended period of time. We weren’t even sure how extended a period of time humans really had to sort this stuff out. We decided to spend out all our resources over the next ten years by putting our ideas and money to work in the Southern communities in which they were most needed, at the rate that the communities could productively absorb them.

We’ve found that taking this limited life approach has sharpened our wits, hastened our willingness to understand and confront problems, and moved us to more quickly locate and develop strong relationships with great partners who will outlast us. We were helped in our thinking about sun-setting by the example of the Beldon Fund, a foundation that closed its doors in 2009, and went to the trouble of documenting why and how they did that. I hope this report, by our friends at the Center for Effective Philanthropy, further advances the field, and encourages more foundations to ask themselves whether sun-setting will help them achieve their goals more quickly and powerfully.

A Date Certain: Lessons from Limited Life Foundations

The limited life approach in philanthropy has received increased attention in recent years. But across foundations, perpetuity is often still seen to be the default, and there is considerable uncertainty about the practice of spending down.

To learn more about limited life foundations’ decisions to spend down — and the ways in which they grapple with several important issues along their journey to pursuing their goals in a finite period of time — CEP conducted in-depth interviews with leaders of 11 limited life foundations.

Resulting from these interviews, this report illustrates the ways in which limited life foundations approach spending down in nine key areas, including investing, grantmaking and strategy, and communications. The research shows that most leaders of limited life foundations choose to spend down because of the belief that it will lead to greater impact. And though these foundations’ leaders wrestle with a similar set of issues in their work, our interviews revealed that there is no one way to spend down.

Accompanying the report is a companion publication of case studies of three of the foundations featured in the report: the Lenfest Foundation, the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, and Brainerd Foundation.

The Early History of F4DC’s Role in Community-Based Efforts to Build a Cooperative Grocery Store at Bessemer Center

Earlier this week, I drafted this history to clear up some confusions about how and when work on the Renaissance Community Coop started, and the role that F4DC has played. We decided to post this history on our website so that more people have access to it during this period when City Council is deciding whether and how it will support the coop. We also thought that in the long term (5-10 years from now), people might be interested to see in some detail the ways that F4DC has chosen to work in its local community. You can see that community organizing of the kind we’re supporting on the grocery store project is connected to long time frames, networks of relationships, and developing ideas.

It’s important to say that this particular written history mainly covers the early work on the coop, which was spearheaded by F4DC. At this point, in 2013, the coop development work is led by the Renaissance Cooperative Committee, to which F4DC provides technical support. But in 2011 and most of 2012, F4DC was playing the leading role, which is why this history is titled the way it is: its emphasis is on the early days, before the RCC had assumed the lead. I eagerly await the history as written by the RCC, which will have its own perspective and community-based flavor!

Since 1998, when the Winn-Dixie closed, Ed Whitfield (co-director of F4DC) and I have independently followed and occasionally connected to Northeast Greensboro residents’ efforts to bring a grocery store to the site of the old Winn-Dixie. Both of us attended early meetings of Concerned Citizens of Northeast Greensboro, just to see what was going on, and to lend our occasional support as private citizens.

In 2010 and 2011, Ed and I established a tighter focus for F4DC’s work, with a strong emphasis on cooperative economics. In the course of entering this arena, we discussed among ourselves the possibility of a community-owned grocery store on Phillips Avenue.

In fall of 2011, Ed and I had a discussion with Goldie Wells (President of Citizens for Economic and Environmental Justice (CEEJ) and founder of Concerned Citizens) about the possibility of a coop grocery store in the site of the old Winn-Dixie. At that time, Goldie wasn’t particularly interested, because she thought Sav-a-Lot was coming in. By the end of that year, it was apparent that the Sav-aLot deal was dead.

In winter-spring of 2011-2012, Ed and Sohnie Black (an F4DC staff member with a personal interest in the grocery store) began mentioning the idea of a coop grocery store in CEEJ and Concerned Citizens meetings. People showed interest, and a few took home copies of a “how to” manual for starting food coops put out by the National Cooperative Grocers Association that we circulated.

In March of 2012, I reached out to Dyan Arkin, the City Planning Department staff member with responsibility for the Bessemer Center, to discuss the possibility of a coop grocery store. It took a while to set up the meeting, but we finally met in early June. Dyan went to some length to help us understand the history of the by-that-time “past due” contract with East Market Street Development Corporation and New Bessemer Associates (the 75% occupancy deal). She encouraged us to give the coop grocery a try, since there seemed to be no other action on the Center at that time.

On July 10th, Ed, Sohnie, and I convened an exploratory meeting with Ralph Johnson, Bob Davis (co-chairs of Concerned Citizens), Wes McGuire, Mac Sims (East Market Street Development Corporation), Jim Kee, and Dyan Arkin, in which we explained how coops work, and asked for their ideas about whether/how to proceed. Goldie Wells was invited to the meeting but was unable to attend.

The very next morning, with no consultation with F4DC, Concerned Citizens or CEEJ, Jim scheduled a press conference at the Bessemer Center, and at least one TV station filmed Jim’s press conference. The news story, which can be viewed in its entirety here, included these statements and quotes:

The Concerned Citizens group who live in East Greensboro is talking about starting a co-op grocery store. In this case it would be owned by investors and people in the community who would also invest.

“The great thing about a co-op is that the community gets to decide what they want in the store, how they want the store to look, how they want the store to operate,” said Kee.

Jim also mentioned F4DC’s role in helping to find financing for a coop grocery store and compared the potential of the Northeast Greensboro effort to the recent successful coop grocery startup in Burlington, Company Shops Market. (F4DC had provided information about Company Shops the night before, as an example of how a community came together to build itself a grocery store.)

In late July and early August, Ed, Sohnie, and I made presentations about the coop approach at CEEJ, Concerned Citizens, and Woodmere Park neighborhood association meetings, to drum up interest for a field trip to Company Shops Market.

On August 8, 2012, F4DC sponsored the field trip to Company Shops Market, and took 2 van-loads of folks from the neighborhood to tour, eat lunch, and talk to a founding board member and the general manager of Company Shops. Jim Kee, Ralph Johnson, Bob Davis, Goldie Wells, and Mac Sims were on the trip, as were many of the people who went on to form the core of the RCC Steering Committee. About 25 people from the neighborhood decided over lunch at Company Shops to continue to explore how they might, as ordinary people working together, form a coop grocery store.

Throughout the fall, these folks met regularly, studied, and got more people involved. Jim Kee attended a few of these meetings. In November, the group decided to formalize its organizational efforts, and voted to name itself the Renaissance Coop Committee, because they knew the name of the shopping center was slated to change and because they liked the association with the concept of “rebirth.” The Renaissance Coop Committee publicized the fact that they would be electing officers at their next meeting in December. A front page Peacemaker article featured the RCC and its efforts.

In its December 3rd meeting, which, like all its meetings, was open to the public, the RCC elected officers and decided to commission a market study, to assess the viability of operating a full-service grocery store. Jim Kee was in attendance at that meeting, and Ed asked him if it was time for the community to formally ask the City to stop seeking a grocery store for the site, because the coop was going to take care of that need. Jim responded that there was no need to slow the process down since it had been many years since the grocery store had closed and there was no progress. “You couldn’t go any slower,” he said. He then went on to say that he wanted to remain open to any and all proposals, but that there was nothing in the works at that time.

Two weeks later, at a specially called CEEJ meeting to discuss the proposed sale of Redevelopment Commission property on Phillips Avenue to Dollar General, Skip Alston made an announcement that he was working with a group of investors who wanted to bring a full service grocery store and a renovated shopping center to the Bessemer Center. He stated that he had been working with Jim Kee on this for a few weeks. When coop people in the crowd asked Skip if he knew that there was a community group interested in opening a community owned cooperative grocery store, he responded that he did not know anything about that. Skip was then asked if his group of developers would be interested in working with the coop in a scenario where the coop group would operate the grocery store and his developers would operate businesses in the remainder of the Center. He responded that his group was not interested in that. “No,” he said. “We want the whole thing.”

The next night, at the December 18th City Council meeting, Jim Kee formally asked City Council to work with the new development group that Skip represented on the proposal that would include giving the ownership of Renaissance Center to Skip’s group of investors. In that discussion he made no mention of the community’s interest in opening a coop grocery store. In his presentation, Jim stated that he had been working with Skip on the project for the past two months.

Epilogue: In mid-February, 2013, Skip contacted the RCC to offer the coop a corner of the grocery store that his group of investors would own and operate and to say that the coop might even have its own cash register there. He was told that the coop was interested in opening a full service grocery store, not just a fresh vegetable section of a larger store. He said that he did not know this. It was later erroneously reported to City Council that Skip’s investors had offered to support the coop and that the coop had rejected the offer.

Since that time, there has been continued work in the community by the RCC leadership group and growing understanding and support for the coop grocery store. Skip and his investors met with the RCC and amended their original offer to say that they are now willing to lease the grocery store space to the coop at the same rates the coop requested from the City. RCC also met with New Bessemer Associates, the developers who are seeking the contract for doing the construction and upfit work on the Center, but are not seeking ownership. They too expressed a willingness to work with the coop and offered the fact that they had built the successful Deep Roots expansion as proof of their competence and willingness to work with coops.

Private investment is private investment, whether it comes from individuals or a community

The Renaissance Community Coop will bring $1.3 million in private investment to Phillips Avenue, and has already raised more than half of that amount.

The Renaissance Community Coop (RCC) is really on a roll! Self-Help Credit Union has stepped up with a term sheet offering $700,000 toward the start up costs for launching a community-owned grocery store in the Renaissance Center on Phillips Avenue. Now, Self-Help didn’t do this out of some charitable impulse. Sure, they’re a credit union with a mission of community development, but they’re also successful bankers who have to properly evaluate and underwrite all the risks associated with any loan they make. Like any bank, they want their money back—with interest.

Self-Help looked at the RCC’s market study, pro forma, and proposal, and decided the coop was a solid investment. A solid investment, that is, given certain conditions, including ongoing City ownership of the shopping center in which the coop will operate. Self-Help added this condition because they think that’s the best situation to nurture the coop and lay the groundwork for an even larger investment in community ownership: the community buying the whole shopping center.

No doubt, the news about Self-Help’s willingness to lend to the coop had a strong impact on Greensboro City Council members. That news, plus the over 100 people who turned out in support of the coop, turned last week’s City Council meeting into a bit of a love-fest for the coop. Virtually every member of Council plus both developer groups declared their support for the RCC effort.

The Council meeting was long and ultimately no conclusion was reached. After more than four hours of listening to the various proposals and public commentary, followed by discussion among themselves, Council members decided to postpone the decision about the long-term ownership of the Renaissance Shopping Center until their June 4th meeting. Whichever way the Council decides (continued City ownership of the Center versus passing ownership to a private developer), it looks like the coop has a home. So I left the City Council meeting pretty happy, even though I was confused about one aspect of the conversation.

Here’s the thing that puzzles me: Again and again, I heard several Council members say in support of the idea of selling the Renaissance Center to a private development group: “In this economy, we can’t afford to turn our back on private investment!” I wanted to jump up out of my seat and yell, “Wait a minute! That’s exactly what you’ll be doing, if you sell the Center to a private developer. Because that’s endangering the $700,000 loan from Self Help, which is explicitly tied to the City retaining ownership of the shopping center or selling it to the community!”

Council members, for the most part, seemed oblivious to the idea that the coop was itself bringing a significant amount of money to the table. Instead, many seemed to be treating the coop as a very worthy, popular, “charitable” enterprise. This was puzzling to me: In the RCC’s presentations to Council and in all the information we had circulated to Council members in face-to-face meetings, we had carefully spelled out our plans for raising the $2 million we needed to open the grocery store. Yes, we are asking for a $100,000 grant and a $600,000 loan from the City. Lots of businesses have asked for and received economic development support of this kind from the City. More importantly, the RCC is also bringing $1.3 million of our own money to the table. That $1.3 million is what any banker would call “private investment.”

Maybe there’s some confusion about this word “private.” When City Council members were throwing the word around in regard to the proposal from the private development group that wants to gain ownership of the shopping center, I think they meant “dollars not coming from taxpayers.” That is the same meaning I am putting on the term when I say that the coop will bring $1.3 million in private investment to the project.

With the Self-Help offer included, the RCC already has $745,000 of our private investment in hand or pledged. That’s a whole lot more than any of the other proposing groups have demonstrated.

And we are well on our way in raising the $600,000 more that we need, from member equity, owner loans, local and regional foundations, and community development financial institutions who specialize in lending to coops. If you want to see the details on our financing plan, check out the “Capital Requirements” worksheet that’s included in the RCC’s pro forma, which is available on the RCC website.

It’ll be a whole lot easier to raise this money when decisions are finalized, assuring the coop has a certain home in the Renaissance Center with the financial backing of the City. Here’s hoping everyone on City Council comes to understand the sizable investment the coop is making in our community, and makes the best decision for the community and the coop!

Resilient Worker-Owned Coops Provide Good Jobs for the Long Term

Next Wednesday, January 26th, F4DC is hosting the second movie in its Film Series on people building grassroots economies anchored in communities. We’ll be showing SHIFT CHANGE, a film about worker-owned cooperatives, at 6 pm at the Carousel Theatre. Click here for more info about the screening.

If you’ve looked around our website a bit, you know that we’re excited about cooperative business as a key to rebuilding the economy. Here I want to say a bit about why worker-owned cooperatives, in particular, can make a difference. On the outside, they seem to function much like conventional businesses: they sell goods and services at a price that allows them to cover their costs (rent, labor, raw materials, etc.), and then some. Like any business, they have to make a profit; otherwise they have to shut down.

It’s this question of profit—its place in the grand scheme of things—that distinguishes worker owned coops from other kinds of businesses. Because the workers themselves own the business, they don’t make business decisions simply on the basis of maximizing profit, like most conventional businesses do (and all corporations are required to do by their very charters). A worker coop’s decision-making is based on the long-term need to sustain the business in a way that keeps providing the worker-owners with good jobs. So, for example, a worker coop isn’t going to up and move to a new location where lower wages prevail.

This isn’t to say that sometimes worker coops don’t have to make tough decisions, even cutting hours, wage rates, or jobs during tight times. This has happened at lots of worker coops around the globe during the current recession. But because the workers themselves are democratically making the decisions, it’s done with an eye to the long-term well-being of the workers as a group, rather than short-term profit-taking.

It turns out that this kind of long-term thinking and democratic governance leads to worker owned businesses having better track records for economic resilience, surviving downturns in greater proportions and making faster comebacks. This has been thoroughly documented in a study (pdf) that analyzed data from 50,000 employee-owned enterprises in 17 countries.

Contrast the inherent “long-termism” of worker-owned cooperatives to the “short-termism” of corporations focused on maximizing profit for shareholders who have no connection to the day-to-day operation of a business or the community in which it exists. Down the road from us, in Rocky Mount, the closure of the Merita Interstate Brands Bakery put 286 people out of work. That’s a lot of jobs in a town the size of Rocky Mount. If you followed the news last November, this closure was part of a national strategy by Hostess, the parent company, to liquidate all its bakery holdings, throwing more than 18,000 workers out of their jobs. Initially, the company tried to blame the liquidation on striking workers, but it later came to light that the company had long planned the closures, well before any strikes took place. Furthermore, Hostess had been owned and managed by a sequence of private equity firms that had no expertise or interest in operating an ongoing bakery business. They were essentially loading the company up with debt in order to pay outrageous compensation to top executives. Oh yeah, and they raided the workers’ pension fund while they were at it.

Could the Rocky Mount bakers – the people who actually do the work of the bakery—operate their own bakery? I don’t see why not: collectively, they know how to work in and operate a bakery, and people will always need bread. Sure, some work would have to be done to develop a viable business model and some money would have to be raised, but that’s what’s involved for anyone who takes over the business. It wouldn’t be the first time workers came together to revive a failed business: former workers at Republic Windows have formed a new worker-owned business called New Era Windows. They have raised money from a broad base of community supporters and unions so they can buy the now-closed factory and its contracts.

I am still weighing whether the strategy of converting failing corporate enterprises to worker-owned businesses can succeed at scale. Some people say that such businesses tend to have been mismanaged for so long that they make for very weak beginnings that are hard to overcome. Other people say that the existence of a group of skilled workers who already know how to work together makes for a good basis for a successful enterprise. It’s probably a case-by-case kind of thing.

In any case: come on out to see SHIFT CHANGE next week, and get inspired about the potential of worker-owned coops! Whether launched from scratch or as a conversion, worker-owned businesses need to be a big part of rebuilding our local economy!

More books, not less! Guilford County parents organize to oppose book bans

About a week ago, some Guilford County residents carried a petition with some 2,200 names on it to the School Board, asking to eliminate controversial books from high school reading lists. They targeted certain books, like Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Isabelle Allende’s House of the Spirits, objecting to sexually explicit passages and what they saw as anti-Christian themes. Actually, using these books as examples, they asked for the school system to revise the entire way it selects books, so that books like these would not ever again appear on reading lists.

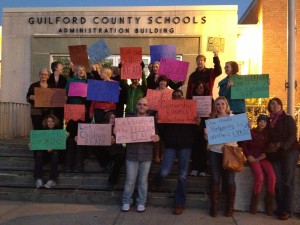

Well, community dialogue and activism is alive and well in Greensboro! In response to this threat of book banning, roughly 30 people marched from the Central Library to the School Board meeting on Eugene Street, carrying signs that read, “More books, not less!” and “Let Our Children Read!” Here’s a picture of some of that contingent when they arrived at the School Board building. Many marchers then entered the meeting, where they addressed the School Board, making sure that the Board knew there was large crew of folks who like the book selection policy just fine.

Book banning is NOT the way to deal with controversy and difference. More democratic dialogue, not less! Hooray!

The Short and Happy Life of the Fund for Democratic Communities

Here’s something you may not have known about F4DC: we don’t plan on being around after 2020. No, we haven’t subscribed to any end-of-the-world doomsday scenarios. In fact, quite the opposite: we’re thinking that the chance of human survival past 2020, perhaps even into the next century, will be improved if we go out of existence!

At this point, you may be thinking, “Whoa! These folks have a curious view of their destructive potential, not to mention their own importance!”

Let me explain.

The vast majority of charitable foundations come into existence under an assumption that they’ll exist forever — “in perpetuity,” is the legal term of art. Under this model, foundations put their money resources — “financial principal” (never to be confused with “financial principles!”) — into investments that deliver interest or dividends or capital appreciation at a level that allows them to give away some money each year, while preserving or even growing the underlying principal.

By law, foundations have to give away or otherwise spend on charitable purposes 5% of their assets each year. Thus, if a foundation has $8 million in assets (about what F4DC’s assets are valued at these days), the US tax code requires it to put $400,000 each year toward charitable purposes.

Here’s the deal. The world is in a real pickle, and dribbling out $400,000 per year just isn’t going to have transformational impact. And we need some transformation!

The global financial crisis is just one of several deeply disruptive, linked crises that together portend a level of environmental, economic, and social collapse that is already radically altering how we live. Whether we want to change or not, big changes are coming — some of them are here already (Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy!) — due to the intersection of climate change, peak oil, and the non-sustainable nature of a global, corporate capitalism that has driven the world toward the greatest wealth inequality ever experienced by humanity. People are hurting, struggling to support their families and communities, as jobs disappear and wages stagnate. Catastrophic weather events escalate in number and severity, pushing communities past the breaking point. Our representative democracy is under siege from corporate interests who are unelected and unaccountable. And our grasp of direct democracy (that is, our community capacity to dialogue about our needs and decide on collective action to meet them) is shaky at best.

In the face of the failing economy, many people are recognizing the need to build a new economy to take its place: one where people and planet come before profits. Where the rewards of productivity go to the people who do the work. Where communities are enriched, not stripped, by businesses that are rooted in place. An economy built on the principles of cooperation, sustainability and solidarity, not competition and exploitation. At the same time, people around the globe and at home in the U.S. are coming together to demand that the voices of the 99% be heard, and in the process are relearning and inventing from scratch new democratic forms.

We’re at a pivotal moment, a time of opportunity on the one hand and real danger on the other. F4DC is striving to put its resources — both money and people power — in service to the massive project of building a just, sustainable and democratic economy in this critical period. It’s a big project, and it’s sure to last way past 2020. But we think F4DC’s greatest impact—our shot at transformational impact—is in these next eight years.

If you’re wondering where this “eight years” figure comes from: Ed and I actually came to this idea of spending down our resources a couple of years ago. At that time, we gave ourselves a ten-year horizon line. Seemed like that was enough time to hatch and work on some serious projects, but also a short enough time frame to concentrate the mind. We’re two years in now, and believe me, the 2020 deadline does indeed concentrate the mind. Our entire staff is struggling to define what it would look like for us to leave a lasting legacy and evaluating whether our program and grant-making activities are on track to achieve it.

Stay tuned: we’ll have more to say about the legacy we hope to leave in later blog posts. For now, just know we’re working with growing numbers of people in our city, North Carolina, and the Southeast (link to the Federation of Southern Coops and SGEP) in ways that we hope position us all to be around a whole lot longer, even if F4DC is no more.

We picture a web of strong people, versed in democratic arts, who are able to work together to rebuild their communities. We see organizations, institutions, and networks across the Southeast that link and nurture democratically-minded economic and political projects that flow from communities that are usually pushed to the margins: Black folks, poor whites, Native Americans, women, immigrants, young people. Imagine a growing pool of autonomous people and organizations who understand that their well-being is tied to the well-being of all, and have a pretty clear idea of how to build a new economy anchored in vibrant democratic communities. We think of F4DC and its resources as part of the “seed capital” for this new venture.

The International Summit of Cooperatives: A Battle for the Soul of the Cooperative Movement?

I just got home from the International Summit of Cooperatives, in Quebec City. My head is still grappling with the people and contesting ideas that swirled around me for four days. Generally, I hate conferences, but I am grateful I went, for a number of reasons, not the least of which that I had a chance to meet brilliant, inspirational coop leaders from other countries, especially Canada.

I traveled to the conference equipped with a long list of names of people whom my Southern Grassroots Economies Project (SGEP) friends told me I just had to meet. I copied all these names out on a card in a feeble effort to burn them into my brain, in the hope that somehow, I’d recognize them in the crowd of 2,800. (Believe it or not, I am shy, so this was frightening to me!) I arrived, picked up my translation equipment and sat down, thinking, “Now what? I don’t know a soul here!” I introduced myself to the woman sitting next to me. She was polite and immediately resumed her conversation with her friends to the other side — in French. I was really starting to sweat it, when a woman who was animatedly speaking with two other people walked down the long row of seats and sat down next to me on the other side. Serendipity! It was none other than Hazel Corcoran, Executive Director of the Canadian Worker Cooperative Federation (CWCF)! Hazel’s name was the top name on every list of suggested contacts that I received in advance of the conference! We introduced ourselves, and over the next three days Hazel made sure I got a chance to meet with just about everyone who cares about worker cooperatives in Canada and on the international scene. Thank you, Hazel!

Through these personal connections and in the course of a vibrant forum on worker coops on the second day of the conference, I became more solidly convinced of the importance of F4DC’s work in the area of worker coop development, as a primary vehicle for democratic, just, and sustainable economic development. I got lots of exposure to the benefits of consumer coops (especially credit unions—they were there in huge numbers) and producer coops. But it became clearer as the week went on how easy it can be for these kinds of coops to lose the thread of democracy. There is something about the worker coop movement — especially its assertion of the “instrumental and subordinate nature of capital” — that keeps worker coops grounded in the democratic principle of one person—one vote and the idea that humanity’s real power lies in our coordinated, productive labor from which we generate community wealth.

Don’t get me wrong — I learned about lots of principled, successful consumer and producer coops at the conference. But I also saw how many coops are coops in name only, especially some of the very large ones. In fact, the dominant paradigm of the conference, as promulgated from the main stage via a stream of “experts” from McKinsey & Co, Deloitte, Price Waterhouse Coopers and the Harvard Business School, was that coops should do a better job adapting to capitalism, and grow (up) into mega businesses using more or less the same unsustainable business practices of the mega-corps. And that we should accept the current capitalist frame as the only possible economy. Sure, these experts conceded, the global financial crisis (or GFC as many called it) shows us that capitalism has had some problems, and maybe capitalism can learn a thing or two about sustainability from coops. But the cooperative model can only ever be a small portion of the capitalist economy. After all — capital has other plans!

What was really encouraging was the steady growth, throughout the four days of the conference, of a noisier and noisier pushback against this paradigm, coming from this very polite crowd! Sonja Novkovic began the critique on the very first morning, asserting that coops needed to guard against becoming part of the problem by developing new kinds of growth models rooted in values. By the last day, several main stage speakers (Jacques Attali, Felice Scalvini, and Ricardo Petrella in the final panel) cogently and directly critiqued the capital-centric focus, and called on the cooperative movement to establish itself as a revolutionary, new kind of economy that will replace capitalism. Whenever any speaker would make a comment along these more hopeful lines, the crowd applauded wildly!

I return to our work in North Carolina and the U.S. South more hopeful than ever, more convinced we’re onto something vital in our focus on cooperative economic development, and absolutely terrified by the work we have laid out for ourselves. Thank heavens we have some more friends around the globe to help us figure it out!

Greensboro Tenants’ Organization Forming!

We’re psyched to see that Greensboro renters are coming together to organize a tenants’ association! Landlord associations have been active in the Triad for a long time, representing the interests of landlords in municipal affairs. Now a countervailing powerbase anchored in the tenant community is coming together! It’s about time – tenants’ groups in other cities have made a huge difference in issues like these:

- Wrongful withholding of security deposits

- Absentee landlords and slumlords who don’t properly care for their properties

- Minimum Housing Code enforcement after RUCO

- Utility hikes (water, Duke Energy) in the face of no earning increases

- Tenants hurt when the homes they rent are caught up in foreclosure

What’s especially cool is that the Greensboro Tenant Association will be run for and by tenants. Tenant advocacy by groups like the Greensboro Housing Coalition is much appreciated, but it needs to be complemented (if not led by) powerful advocacy and organizing by the very folks most affected–renters!

An organizing meeting will be held Saturday, July 7th at 10 am at Spring Garden Bakery, Corner of Chapman and Spring Garden. Download their flyer for more details (pdf).

Developing a Comprehensive Approach to Trash for the City of Greensboro

With helpful feedback from MaryEllen Etienne of Reuse Alliance

We are happy to report that it looks like White Street Landfill is not going to be reopened! Through solid community organizing that garnered allies from across the city to the “Keep White Street Closed” side of the fight, plus a sea-change in the make-up of the City Council, it looks like the idea of reopening White Street Landfill is off the table. We hope for good.

Now what?

There is important work to be done in our city to come up with democratic, just, and sustainable approaches to our trash. That’s right, I claimed it — it’s our trash, and we have to deal with it—all of us, not just the people who happen to live within smelling distance of a landfill.

And it’s not just about where we will put our landfill—we have to think through the whole trash picture, asking questions like, Where does our trash come from? Why are we producing so much of it? And what can we do to reduce our waste stream so we’re not facing a trash crisis again in ten, twenty, fifty, or one hundred years?

We have a rare window of opportunity here, a confluence of events and conditions that make it possible for us to think big about this topic. Our solid waste contracts are up for consideration (regular waste as well as our contract with FCR, the firm that handles our recyclables). At the same time, a new City Council has just been sworn in, a reflection of massive dissatisfaction with the divisive politics waged in the most recent “trash fight.” Plus, across the country and here in Greensboro, there’s a growing sense of openness and engagement, as people start to wonder if “business as usual” is going to work in a time of economic, environmental, and social crisis.

So, instead of “business as usual,” let’s act now to use this window of opportunity to build a whole new approach to our trash, one that is democratic, just, and sustainable.

As part of F4DC’s commitment to deepening our understanding of democracy, justice, and sustainability, we invited people from across Greensboro to visit Catawba County’s Landfill and Eco-Complex on November 4th of this year. Twenty-four people took us up on this offer. We thought we’d learn a lot by seeing how another North Carolina county handles its trash, and we did! But what was perhaps more important was the time we spent together on the van ride to and from Catawba, and getting a chance to relax and talk together over dinner on the way home. New friendships were formed and lots of ideas were exchanged. Here are a few ideas, ranging from concrete policy recommendations to more exploratory suggestions to guidelines for our decision-making process, which I’ve been mulling over since that trip:

- Extend the current contract with Republic Services through June 2013 to give us time to thoroughly study and come up with a comprehensive approach to solid waste.

- Negotiate a contract extension with FCR, to give us time to thoroughly study and come up with a recycling plan that allows for a significant decrease in the amount of trash heading to the landfill.

- Get the new City Council to take a field trip to the Catawba Eco-Complex, both to see what another community has done, and also to get the benefit of thinking together about trash as they ride down and back. F4DC is willing to help organize such a trip, if that is helpful.

- Appoint a citizen/staff task force on solid waste (perhaps in conjunction with the Community Sustainability Council?) to study and recommend comprehensive approaches to our trash that are governed by “seven generations” thinking—that is, developing an approach to trash that our great, great, great, great grandchildren won’t be sorry for.

- Learn from other cities that are more progressive/visionary about this than we are. The City of Austin, Texas would be a great place to start, followed perhaps by San Francisco. We shouldn’t limit our search for ideas only to the U.S. either. In some cities around the globe (e.g., Cairo) over 80% of the waste stream is being recycled, lessening the need for landfill space significantly, creating job for hundreds, and making cheap resources available to industry. Why should we settle for 15% recycling, when 80% is possible?

- Put everything on the table for re-consideration! This includes the implicit and explicit incentives we give to households and businesses about trash. We may not need to move to a mandatory recycling program if we set the incentives correctly. For example, what message do we send when we pick up regular trash once a week, and recycling every other week? If we flipped this arrangement, it might incentivize people to do a better job separating their recyclables. Or, consider a different fee structure for waste pickup, one that rewards the household that creates less waste. Using clever incentives and pricing, Catawba County and other towns have found ways to encourage voluntary recycling and reduce the flow of waste into their landfills.

- Build trash policy around the “Four R’s:” Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Rot. We generally concentrate on recycling, but we need turn out attention to the other “Rs” if we’re going to shrink our need for landfill space. We need to educate the public on “reduce” – giving people easy ways to reduce their waste. We also need make residents and businesses aware of existing “reuse” opportunities in Greensboro, and provide resources that help support and grow the reuse sector. And yes, I included “rot” in the list. Organics account for nearly two-thirds of solid waste stream. By keeping food and other organic wastes out of landfills, we can make organic material useful for commercial and residential soil amendments.

- Think about trash and the costs associated with trash in a more holistic and comprehensive way, considering jobs, economic development, and long-term sustainability as essential parts of the “bottom line,” e.g.:

- FCR is proposing to invest in high tech mechanization in its next contract with the City, but is this really cost effective over the long run and in the big picture? Such mechanization may result in jobs being lost as machines replace human “pickers.” Some research suggests that human pickers are needed to achieve high recyclable levels (the machines are just not that smart or flexible) and thus reduce the amount of trash heading to landfills. I am not sure of all the trade-offs here, but the City should consider these factors as it designs its next contract with its recycling firm.

- Consider the triple bottom line benefits (economic, environmental, social) of reuse and recycling in deciding how much to emphasize these approaches in our trash policy. Reuse, in particular, can have a huge economic impact, as can be seen in these statistics: If you take 10,000 tons of materials, and:

- Incinerate it, you create 1 job

- Landfill it, you create 6 jobs

- Recycle it, you create 36 jobs

- Reuse it, you create 28-296 jobs (depending on materials)

- Can jobs focused on community education on trash reduction, reuse, and recycling pay wholly or partly for themselves, through sale of recovered materials and reduction in costs associated with landfill trash? Currently, most Greensboro households and businesses are not participating fully in our recycling program, so there is a lot of potential for growth here, if such education led to significantly improved levels of voluntary compliance with recycling.

- What new community-based businesses can we grow from our trash? For example, are there business possibilities in the rich organic waste from our kitchens (waste that currently creates most of the greenhouse gases coming from our landfills) and the reusable building materials that come from deconstructed buildings? What about specialty businesses that exploit any number of “undiscovered” recyclable materials?

- Can Greensboro become an innovative leader in developing new markets for recycled materials, and through this attract new business to the region?

- What role can the City play in reducing the amount of unnecessary packaging of consumer goods, packaging that is taking up space in our landfills? Every ton of packaging that does not go to a landfill saves us tipping fees as well as slowing the rate at which any landfill gets full. Perhaps we can consider packaging bans (e.g. 100 cities across the US have banned Styrofoam).

- Is it possible for Greensboro to convert its transfer station into an eco-park or zero waste facility# where all of its reusables and recyclabes can be recovered and not exported as waste? This idea is worth exploring.

- Engage people from across the City in meaningful learning and dialogue about a full range of options concerning our trash. We need to make more use of truly participatory processes, with genuine back and forth dialogue, for identifying issues and trade-offs in the trash debate.

- Acknowledge and make use of local experts: City staff (the professionals who wear suits to work and the professionals who pick up our trash), university professors, and ordinary citizens who’ve made it their business to understand the science, business, and logistics of trash, landfills, and hauling. One good place to look for grassroots expertise is in the ranks of Citizens for Environmental and Economic Justice, who have had to learn quite a bit about trash in order to make sure the landfill didn’t get reopened.

- Work to engage everyone in the city—not just people who live near potential landfill sites—in solving the dilemma of what to do with our trash. One possible motto: If you create trash, then you should be thinking about where it goes and doing your part to reduce the waste stream.

Finally, I hope that we will remember that our city, Greensboro, is woven into a larger fabric of people and places who are just as deserving of democratic, just, and sustainable lives as we are. I know there is a lot of discussion about the potential for negotiating a “regional solution” that would have the bulk of our trash going to a facility in Randolph County. While such a solution makes it possible keep the White Street landfill closed, it also lands our trash in another community, one that is just as concerned about their health and quality of life as we are here. It may be a community that has historically been marginalized, just as the White Street community was. Moving trash from one marginalized community to another marginalized community is just not a good enough solution.

It’s a real dilemma – there are lots of places that are suffering economic downturns to the degree that getting a big trash contract might feel like a “good deal,” at least to some people. And there are certainly businesses in Randolph County and other places that would like to profit from our need to do something with our trash. But just because some folks in a different county think it’s a good idea doesn’t make it an idea with integrity. Let’s make sure that the people in such communities have been fully informed and heard in their own city and county deliberative processes. Let’s make sure we know all the details about where our trash might be going and what communities it might impact.

Our collaborative engagement with communities and people—not just businesses—in any place receiving our trash can lead to better landfill design and construction, higher standards on heath and safety, living wages for people just like us, and more sustainable relationships that can help keep the partnership going for a second and third contract. This, in turn, can help us keep White Street closed forever.